Somewhere along the line, perhaps when Cary Grant started talking about LSD, someone decided that merely alluding to the dirty side of life was skirting the issue altogether. Suddenly it was naïve for a character to clear her throat in place of blurting out the f-word in the face of her lover. Today we giggle at the sight of Lucy and Ricky sleeping in separate beds; but what have we got in its place? The belching and farting of Married with Children. I’m not saying that both these shows aren’t funny, but the question I’ve found myself asking is: Is a show like Married with Children any less naïve than I Love Lucy?

Literature is worse. Once upon a time, not long after the Hays office conquered Hollywood New York Hollywood Sodom

And, in turn, what is the attitude of this new author toward the film industry? Does he care about the fate of his story? What is the “state of affairs,” so to speak? I read an article recently in Poets & Writers Magazine about novels and film rights. According to Jonathan Franzen: “I know too much about Hollywood—about Hollywood adaptations of novels, about novelists with Hollywood—to have hopes of anything much besides getting paid. My chief hope is that a movie of The Corrections gets made but not before the option has been lucratively [sic] renewed a few times.”

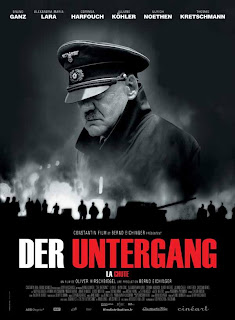

Allow me to name a few director-author collaborations that worked: (1) Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita co-scripted with Vladimir Nabokov, (2) William Friedkin’s Exorcist co-scripted with William Peter Blatty, (3) Elia Kazan’s Viva Zapata! co-scripted with John Steinbeck, or, in Germany

In the same magazine, I read an article by author David Long who said of symbolism: “To be honest, I’m not wild about symbolism. I don’t like the notion that behind what floats on the page there’s a ‘true meaning’ to be extracted, that the writer has fashioned not an art object but a puzzle, a code¼it reeks of Middle Ages theology¼I happen to like the here and now.” Again, I’m left speechless. One of the most beautiful things about art—if not the most beautiful thing—is that it inspires us to think. Take away the symbol and all you’re left with is a pretty picture.

Oscar Wilde said: “All art is at once surface and symbol. Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril.” This may be true, but have you ever considered the contrary? Oh cow, the pasture of prettiness awaits you! Even Oscar Wilde couldn’t survive in such a tedious state (perhaps that’s why he wrote The Critic as Artist). Superficiality is the Shangri-la of weary intellectuals, dried-up poets, nihilists and cynics; anyone with the desire to live will venture into the depths, even when it is perilous.

In my early twenties, because I was ignorant of the context, I had a difficult time appreciating medieval art. Now I find with each year, each visit to Prague

And yet this attitude is omnipresent today. Take movies, for example, which constitute the primary spiritual staple for many people. Since the mid-seventies (since Jaws, Rocky and Star Wars) Hollywood Wuthering Heights Hollywood Hollywood New York City

During the fifties, when censorship began to dissolve, filmmakers found themselves with greater freedom to express themselves; and possibly most important of all the changes to be wrought by the mavericks, iconoclasts and smugglers of this era was an overdue revolution in the psycho-sexual drama. I shouldn’t say “wrought by” but rather “helped along by,” because there were at the time many other forces—from the Kinsey report to Playboy magazine—helping to change the mores of America

Soon after, however, the age of Rambo arrived (Clint Eastwood morphed into Dirty Harry, Charles Bronson acquired a death wish); the studios collapsed like temples atop Olympus , and quality films became fewer and farther between. I’m not saying that good films never turn up—Goodfellas, Boogie Nights, Deconstructing Harry and Man on the Moon are all, in my opinion, great escapes. And yet how many times have I been bored by drab acting, numbed by cheesy soundtracks and enervated by arrhythmic editing? A picture may be worth a thousand words, but it possesses no temporal value. Its thousand words add up to a single, static idea. Only a story—drama—may enter the realm of time; and, as soon as we speak of two pictures, we are dependent on the literary mind.